By Prudence Soobrattie

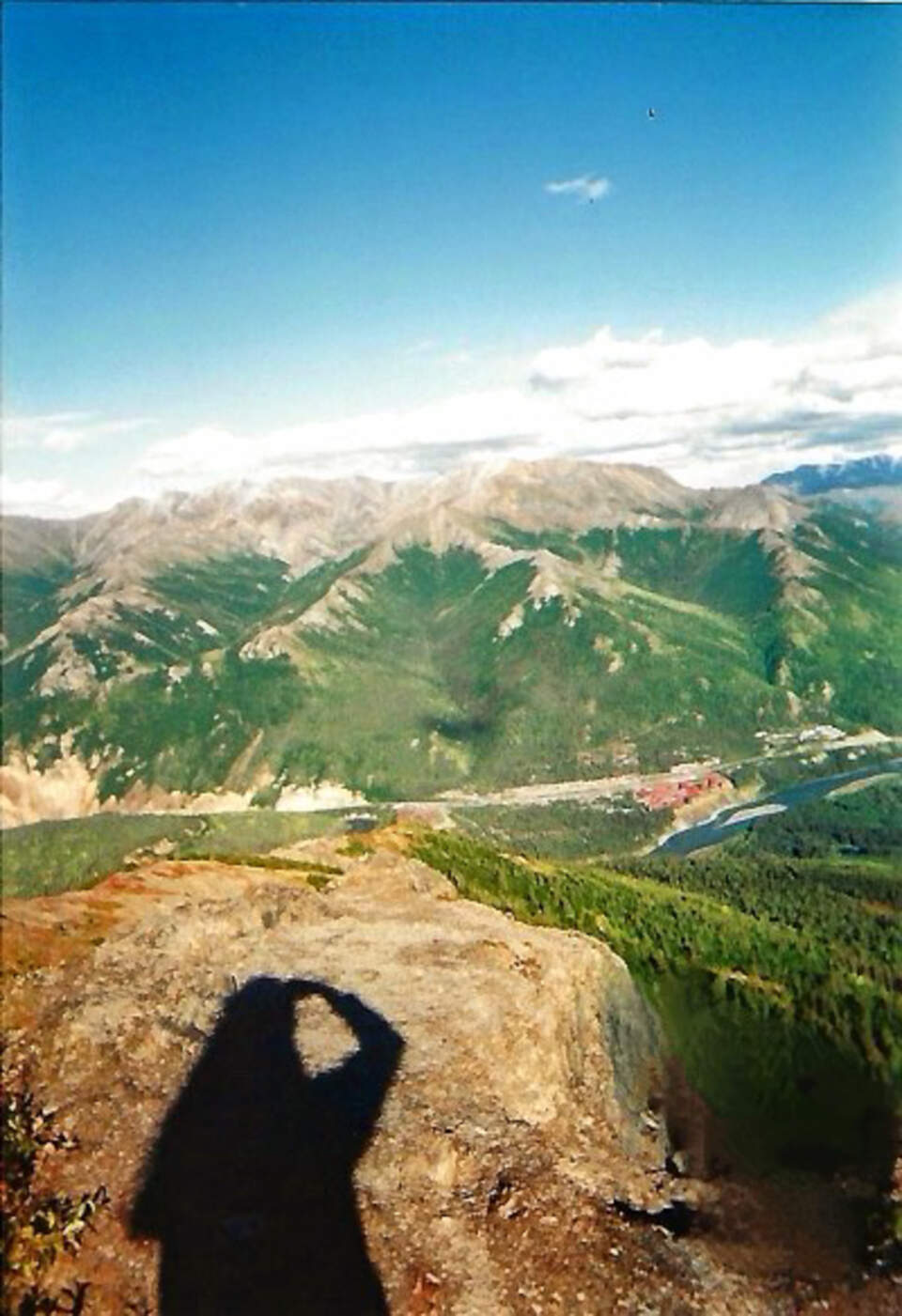

Brooks Range silhouettes, spine of stone holding up the evening.

On my 25th birthday I lay naked on the Alaskan tundra. Nestled upon soft organic matter, generations of lives beneath me, I felt reassuringly connected. It was the most memorable celebration of my anniversary on Earth.

It was the most memorable celebration of my anniversary on Earth.

At the cannery, my bunkmates surprised me with a six-pack of beer wrapped in pink ribbon. It was a superfluous gift since while waiting for the salmon to run, absent of any work, we went out drinking every night. At the Fisherman’s Bar we waded into a sea of musty odors, salt water from a day’s work, yeast from glowing amber pints strewn about like candles in a church. When we yearned for a whiff of something unfettered, we sat on the ridge near the river, waiting for bears. Hungry, they ransacked the trash cans below eager to find something to sate their appetite.

Earlier that day, I stopped by the post office to pick up a homemade cake my mother had sent. During its long travels, it had grown a bit moldy. My mom could’ve reminded me to get the cake sooner had it not been 2015, a time before universal cell phone coverage. Isolation was one of the reasons I’d ventured to Alaska. A fascination with salmon was the other.

Primordial insight drives the salmon’s homecoming pursuit of procreative suicide. So arduous is this endeavor that organs of the still living fish begin to decay. As their flesh disintegrates, they begin to resemble zombies—much like my birthday cake.

As their flesh disintegrates, they begin to resemble zombies—much like my birthday cake.

Sneaking away to celebrate in solitude wasn’t a problem, since we hadn’t begun working. Weeks passed as we awaited the fish. During this time, when we questioned our existence as canners, the supervisors admonished us to be prepared. Salmon could run any moment, and like Minutemen, we had to be ready when they did. Even if that moment occurred during the night, we were expected to jump out of bed, don our waterproof garb, and hustle from the barracks to the cannery.

Gloved hands at the trimming table, knives flashing over steel.

We were young people from all parts of the “lower 48”, short-term imports to fill the local worker shortage. A fishy militia, we played games, hooked up with each other, drank, and stared at the river while awaiting our calling. Once the salmon ran, we would work, no matter how long it took or how fatigued we became.

Our drive had to match that of the salmon. The rhythm of our lives was controlled by the instincts of fish who were attentively listening to nature. Humans might not hear nature’s rhythm clearly, but we’re still beholden to it.

Amid an unfamiliar group of seasonal workers, instinct led us to segregate into cliques. Despite our vast human intellect, even our bedtime wasn’t fully in our control. We, along with bacteria, insects, mammals, and fish, had adjusted our bodies to the daily rotation of the planet eons ago. This circadian rhythm was the reason why I had trouble falling asleep upon seeing the bright midnight of Alaskan July.

River like a ribbon—silver bends winding toward the salmon’s upstream fate.

People thought quitting my job and moving to Alaska was illogical. “Are you crazy? Think of your career, your future, instead of chasing adventure!”

There was no way to explain myself. Compulsion is feeling; it cannot be rationalized, only experienced. In retrospect, their logic was flawed. There wasn’t much adventure in the small town of Nanek, Alaska. Most days were quiet, just like this one.

On the afternoon of my birthday, the salmon were out in the ocean, perhaps dreaming of the spawning grounds where they would meld their DNA to reform life from death.

Since the fish were still en route, I decided to wander the vast plains of the tundra. Summer had made the ground lush with green moss. The thawing permafrost was lightly damp and spongy; it gave way with a strange bouncy texture underfoot. Having walked far from the road, I found myself on a level landscape of green, dotted with small shrubs and mounds of tussock. The gentle springiness of the ground created a desire to rest. Longing to feel the earth directly, I undressed before laying down. It amazed me that such a place existed. The ground was soft, welcoming, and in its swaddling embrace I melded with the limitless sky.

It amazed me that such a place existed. The ground was soft, welcoming, and in its swaddling embrace I melded with the limitless sky.

There were no people, not even objects of humanity like buildings or roads. Breathing in, I relished the cool aroma of the atmosphere mixed with the fertile soil below. Shades of blue, as varied as the tiny forget-me-not flowers that adorned the tundra, wandered the winds.

I was both miniscule and immense.

Bunkhouse banter—cards on a milk crate, laughter bouncing off metal bunks.

At length, the hum of an engine from a low flying plane caught my attention. It was a glider with a single pilot. Blocking the sun with my hand, I squinted to examine the cockpit. A man, alone, flew the vehicle. I wondered what he would think of me, this woman lying naked in the middle of the tundra. “It’s my birthday!” I yelled, waving.

“It’s my birthday!” I yelled, waving.

He waved in response as he flew away.

Though my voice couldn’t carry over the distance, I was convinced we communicated. My reason for being on that field, at that moment in time, had been conveyed.

And because the sky he flew is never ending, perhaps he understood.

This story won the 2025 Alaska.org Story Contest prize for the category of "Off-Grid, Off-Road"